Written by Frederic Sabater Pastor, PhD

CTS Ultrarunning Expert Level Coach

With snow melting off mountain peaks, the time for high-altitude trail races like the Hardrock 100 and Leadville 100 is approaching! If you’re preparing for these races or others that feature elevations above about 6,000 feet, here are strategies to employ to have a great race.

Quick “TL;DR” Summary:

- If you have the time and means, move to your race elevation (and venue if possible) three to six weeks before the race, with longer exposures being better.

- If you cannot travel to altitude at least six days before the race, show up the day before.

- If you plan to arrive just before race day, try a heat training protocol in the 10 days beforehand.

- Short altitude camps (one to three days) are helpful for learning how your body responds to altitude.

Physiological Effects of Altitude Exposure

You didn’t come here for a physiology lesson, so I’ll keep this brief. As altitude increases, air pressure decreases, leaving fewer oxygen molecules in a given volume of air. As a result, a lungful of air contains less oxygen at high elevations compared to sea level. For example, the amount of oxygen in a lungful of air in Leadville, Colorado (alt. ~10,000 feet) is only 68 percent of what you’d obtain at sea level. This makes it more challenging to supply oxygen to working muscles at the same rate you could at sea level, which leads to decreased performance at altitude.

The reduced partial pressure of oxygen in the air at altitude has further consequences: people who travel from sea level to elevations above 5,000 feet often experience mild to moderate symptoms of altitude sickness, including headache and/or dizziness. It is also common to have trouble sleeping, and there is greater risk of dehydration from a combination of increased breathing rate and lower humidity. So, short of moving to the mountains (which isn’t necessarily a bad idea anyway 😉), how can ultramarathon runners best prepare for races at higher altitudes (i.e., ranging from 5,000 – 12,000 feet above sea level)?

How To Prepare to Race At Altitude

Strategy #1: Spend three to six weeks at altitude

The sure-fire way to adapt to altitude is to live there. To acclimatize completely, athletes need to spend at least three weeks, and perhaps up to six weeks, at elevations between 5,000 – 8,500 feet. Higher isn’t always better because the higher you go the harder it is to train effectively, sleep soundly, or recover effectively. The primary adaptation you’re after by moving to altitude for three to six weeks is an increase in oxygen carrying capacity through the development of more red blood cells. However, your training volume and intensity must decrease while you’re acclimating. Moving to altitude for one to two months isn’t an option for everyone, but it is becoming more feasible for people who can work from anywhere.

Strategy #2: Travel to altitude five to 10 days before competition

If you can’t spend one to two months at altitude, there are still benefits from a shorter stay in the mountains. The sweet spot is traveling to the venue five to ten days before the race. That way you’re there long enough to get past the detrimental initial effects of altitude that appear over the first two to four days, including acute dehydration, trouble sleeping, fatigue, and headaches. These symptoms lessen considerably as plasma volume adjusts to the altitude. You can also use this time to recon the racecourse and learn to adjust your pacing strategy.

Strategy #3: Race immediately upon reaching altitude

If you don’t have time to acclimate, your best strategy is to spend very little time at altitude before your event. Arriving within 24 hours before your race start can be a good solution because you compete before you experience the initial negative effects of altitude exposure.

Strategy #4: Weekend altitude camps

Short training camps at altitude can be helpful for learning how your body responds to altitude exposure. You’ll learn what to expect in terms of heart rate, breathing rate, and RPE at certain paces and how they change as you go higher. And you’ll learn to adapt hydration and fueling strategies, and probably discover some new aspects of grit and mental toughness.

Strategy #5: Simulated altitude at home

Athletes who want the physiological adaptations from long-term altitude exposures without traveling to higher elevations can try spending time in hypoxic environments at sea level. This can be accomplished through altitude tents/rooms (a plastic canopy that fits around your bed, linked to a hypoxic generator, which decreases the amount of oxygen in the air inside the tent). It’s important to note that not everyone experiences positive outcomes. The generators can be noisy and the environment can be stuffy and you have to spend 8-16 hours per day in the hypoxic environment. Reductions in sleep quality, recovery, and training quality can outweigh the potential benefits of developing more red blood cells.

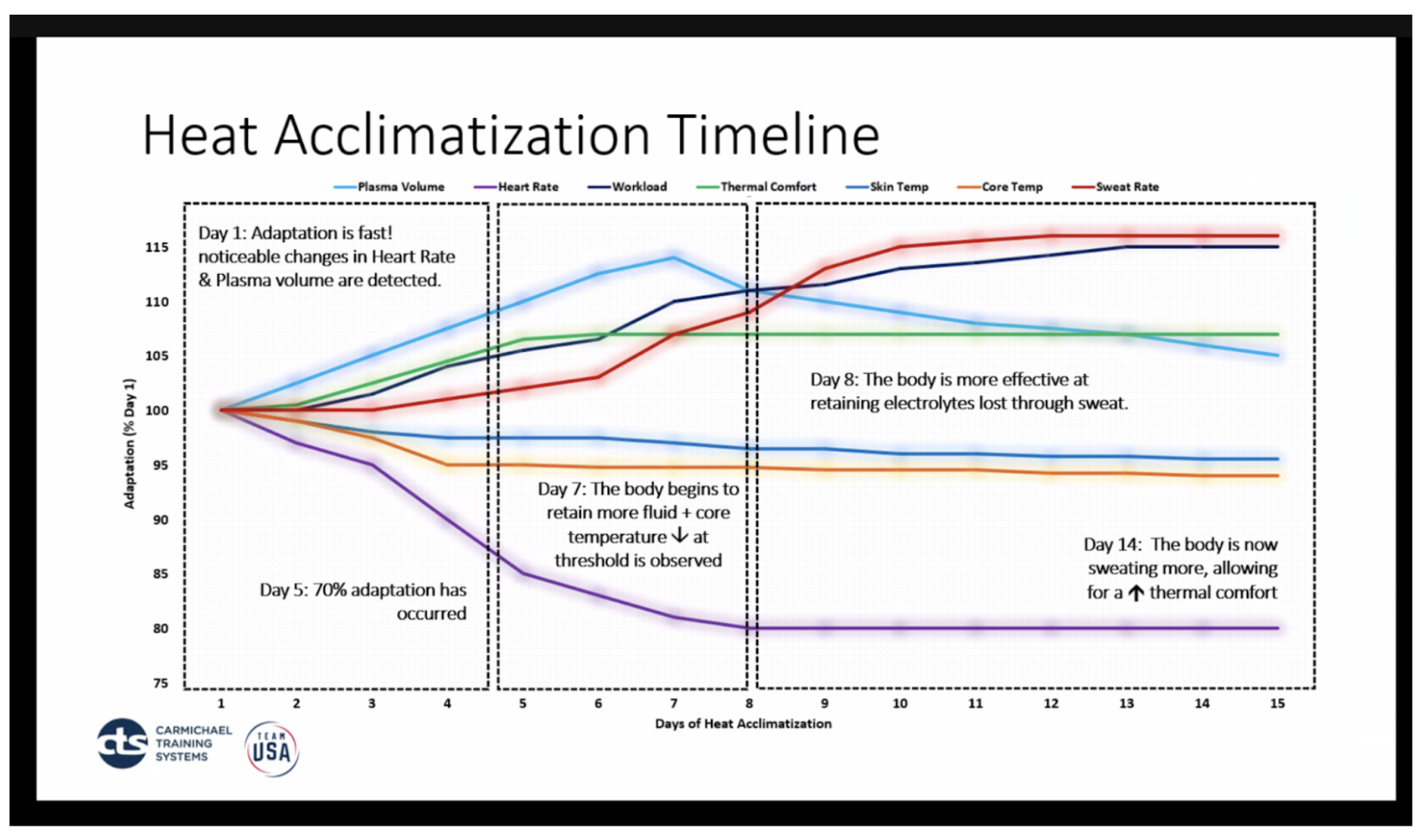

Strategy #6: Cross acclimation with heat exposure

One final strategy that may be helpful is heat training. Although the research is not conclusive and the mechanisms are not fully known, studies have shown that a five- to ten-day heat training protocol (mainly training indoors in hot conditions) in the 10 days before a trip can help diminish the loss of performance at high altitude.

Considerations Before Altitude Training

If you plan on spending time living or training at altitude, keep the following in mind:

- Potential harmful effects include loss of sleep quality, nausea, dizziness, headache, and dehydration. Watch for these, and reduce training load if they happen, let your body adapt.

- Monitor hydration status, hydrate more than you would at sea level, and watch your urine color.

- Check iron levels before a prolonged altitude camp. Consult with your doctor, try to get a blood test, and make sure your iron levels are not low before going to altitude, otherwise you won’t have enough of the building blocks to build new red blood cells.

- You will be slower at altitude, even after acclimating. You will need to account for that, and you won’t be able to run at the same paces you run at sea level. Let go of your ego and use rating of perceived exertion to control your training and racing intensity.

- Altitude is an extra source of stress. Therefore, you will need to decrease your training load when you first go up to altitude. This may mean decreasing volume and intensity.

- Yourwearable devices may help you get an idea of your rate of adaptation. This may be useful for long-term camps, but also for shorter one- to three-day camps, allowing you to track whether you adapt quicker to altitude after subsequent trips.

Frederic Sabater Pastor is a CTS Ultrarunning Coach with a PH.D. in Exercise Physiology and experience coaching athletes for a variety of challenges. He is also a Postdoctoral researcher at the Inter-university Lab of Human Movement. His areas of focus are running, trail, performance, physiology and fatigue.